Choosing between titanium and stainless steel for custom metal parts is not merely a preference—it is a critical engineering calculation that balances mechanical performance, environmental resilience, and manufacturability.

For a design engineer, the decision dictates the component’s lifecycle and failure modes. For us on the manufacturing floor, it dictates the tooling strategy, cycle speeds, and cost per unit. While titanium is often lauded for its aerospace pedigree, stainless steel remains the workhorse of industrial infrastructure. This guide dissects the technical trade-offs between these two material families from a precision machining perspective.

Table of Contents

Titanium vs Stainless Steel: Key Trade-offs

Custom Metal Parts: Material Selection

Selecting the optimal material for custom metal parts requires a holistic view of the “Triangle of Constraints”: Cost, Performance, and Manufacturability.

Titanium and stainless steel alloys occupy distinct niches in this triangle. The choice relies heavily on the specific application environment—whether the part will face galvanic corrosion, cyclic fatigue, or extreme thermal gradients.

- Titanium Alloys (e.g., Grade 5/Ti-6Al-4V): These are selected when specific strength (strength-to-weight ratio) is the primary driver. They offer superior fatigue resistance but introduce significant machining challenges due to low thermal conductivity.

- Stainless Steel Alloys (e.g., 304, 316L, 17-4 PH): These are chosen for their versatility, weldability, and cost-efficiency. They offer high ductility and ease of fabrication, but punish weight-sensitive applications due to higher density.

Comparative Snapshot for Engineers:

| Factor | Titanium Alloys (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V) | Stainless Steel Alloys (e.g., 316L) |

| Environmental Resilience | Excellent: Virtually immune to chloride pitting and crevice corrosion. | Moderate to Good: 316L resists chlorides, but 304 may pit in marine environments. |

| Thermal Conductivity | Low (~6.7 W/m-K): Heat concentrates at the cutting edge, accelerating tool wear. | Moderate (~16 W/m-K): Better heat dissipation allows for higher cutting speeds. |

| Corrosion Mechanism | Stable oxide film (TiO2) forms instantly, self-healing. | Passive chromium oxide layer, requires oxygen to maintain passivity. |

| Raw Material Cost | High: Approx. 5-10x the cost of stainless steel by weight. | Low to Medium: Commodity pricing makes it scalable for mass production. |

| Machinability Rating | Difficult: Requires rigid setups to prevent chatter due to low modulus. | Variable: 303 is free-machining; 304/316 are “gummy” and prone to work hardening. |

Engineering Insight: If your component interfaces with carbon fiber composites (CFRP), titanium is often mandatory due to galvanic compatibility, whereas stainless steel may cause galvanic corrosion in the aluminum or the CFRP itself.

Performance Overview

How Material Properties Dictate Function

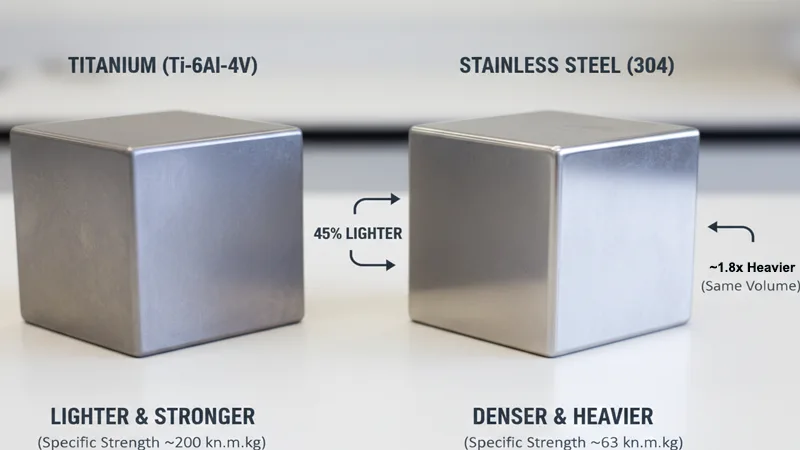

The performance dichotomy between these metals is best understood through their physical constants. Titanium is not “stronger” in absolute terms than high-strength steel, but it is significantly more efficient per unit of mass.

- Titanium: Known for a high strength-to-density ratio. A Ti-6Al-4V part can match the tensile strength of many steels while reducing total assembly weight by 45%.

- Stainless Steel: Alloys like 17-4 PH (precipitation hardening) can be heat-treated to exceed the ultimate tensile strength of Titanium Grade 5, but at a severe weight penalty.

Technical Comparison Data:

| Metric | Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) | Stainless Steel 304 (Annealed) | Stainless Steel 316L (Annealed) |

| Density (g/cm³) | 4.43 | 7.93 | 8.00 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | 880 – 920 | ~215 | ~170 – 290 |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | 900 – 950 | ~505 – 515 | ~485 |

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 114 (More flexible) | 193 – 200 (Stiffer) | 193 (Stiffer) |

| Hardness (Rockwell C) | ~36 HRC | < 20 HRC (Base) | < 20 HRC (Base) |

| Specific Strength (kN·m/kg) | High (~200) | Low (~63) | Low (~60) |

Key Structural Differences:

- Density & Weight: Titanium’s density (4.43 g/cm³) is nearly half that of Stainless 304 (7.93 g/cm³). For rotating components (like impellers) or reciprocating mass, this weight reduction drastically lowers inertial forces and energy consumption.

- Elastic Modulus (Stiffness): Stainless steel is roughly twice as stiff as titanium (200 GPa vs. 114 GPa). If a part must hold strict dimensional tolerances under load without deflecting, stainless steel is often the better structural choice unless the geometry is increased to compensate for titanium’s flexibility.

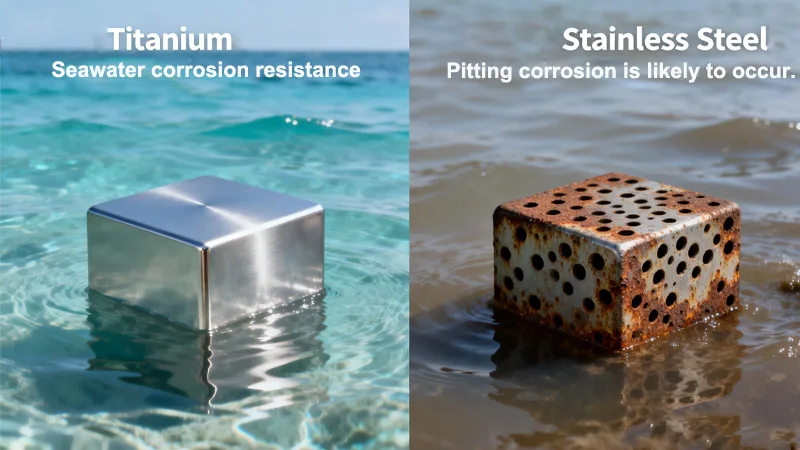

Corrosion Context: Titanium is practically immune to seawater corrosion due to its stable oxide layer, lasting 20+ years in subsea conditions. Stainless 316L is “marine grade” but still susceptible to pitting if water is stagnant or de-oxygenated.

Machinability Impact:

- Titanium: Tool life is the limiting factor. We typically see tool changes every 30–45 minutes of contact time if parameters aren’t optimized.

- Stainless Steel: Chip control is the limiting factor. Long, stringy chips can mar surface finishes, requiring chip-breaker tooling.

| Material | Machinability Rating (AISI B1112 = 100%) | Typical Cutting Speed (SFM) | Coolant Requirement |

| Titanium (Gr5) | 15% – 20% | 150 – 200 | High Pressure (1000 psi+) |

| Stainless (316L) | 45% – 55% | 300 – 500 | Standard Flood / High Pressure |

Machining Custom Metal Parts

Machinability of Titanium Alloys

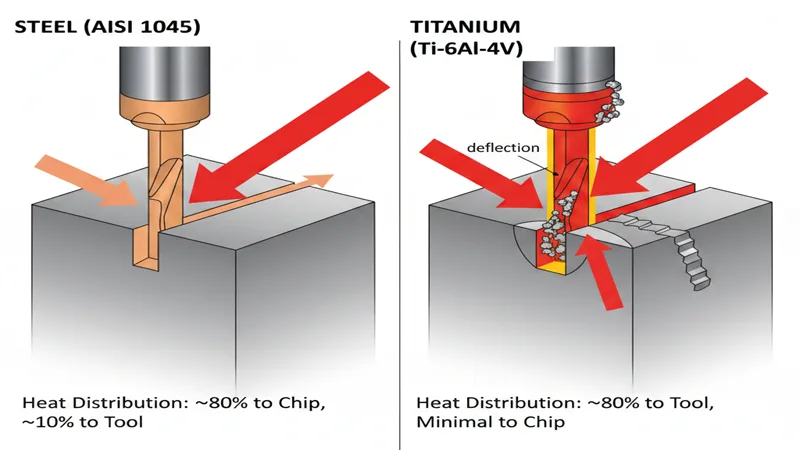

From a machinist’s perspective, titanium is “gummy” yet abrasive. The primary challenge is heat management. Unlike steel, where ~80% of the heat is ejected with the chip, titanium conducts heat poorly. Consequently, about 80% of the generated heat transfers into the cutting tool, leading to rapid thermal failure (cratering).

Critical Machining Protocols:

- Low Thermal Conductivity: We must run lower surface footage (SFM) to manage edge temperatures.

- Galling (Adhesion): Titanium tends to weld itself to the cutting edge (Built-Up Edge), leading to poor surface finishes and sudden tool breakage.

- Low Modulus: Because titanium is “springy,” it tends to bounce away from the cutter. This causes chatter and dimensional inaccuracy. Heavy workholding and rigid machine setups are non-negotiable.

Tool Wear & Cutting Speed

To machine titanium economically, we employ specific strategies:

- Small Radial Engagement: We use dynamic milling paths (high axial depth, low radial cut) to keep the tool cool.

- High-Pressure Coolant (HPC): A coolant blast directly at the cutting zone is essential to fracture chips and evacuate heat.

- Positive Rake Angles: Sharp, positive geometry reduces cutting pressure and heat generation.

| Challenge | Titanium Alloys | Stainless Steel |

| Thermal Load | Extreme: Heat stays in the tool. | Moderate: Heat dissipates better into chips. |

| Chemical Reactivity | High reactivity with carbide at temp; requires TiAlN coatings. | Generally stable; abrasive wear is common. |

| Work Hardening | Skin hardens if the tool dwells; requires constant feed. | Significant in austenitic grades (304/316). |

| Chip Evacuation | Thin, ribbon-like chips; dangerous if not broken. | Stringy chips; needs aggressive chip breakers. |

Heat Generation & Cooling

In titanium machining, dwelling is fatal to the tool. If the cutter stops moving forward, the material work-hardens instantly, and the subsequent cut will shatter the tool edge. We maintain a constant “Chip Load per Tooth” to prevent rubbing.

Machinability of Stainless Steel

While generally easier than titanium, the 300-series (Austenitic) stainless steels present their own difficulties. They are characterized by high ductility and a tendency to work-harden rapidly.

Tool Life & Efficiency:

- Speed: We can run Stainless 304/316 at nearly double the speed of Titanium.

- Mechanism: Failure is usually due to notch wear at the depth-of-cut line or built-up edge (BUE).

- Optimized Grades: Using 303 (contains sulfur) drastically improves machinability but sacrifices weldability and corrosion resistance. 304 remains the standard but requires rigid setups to prevent vibration-induced hardening.

Surface Finish & Tolerances

Stainless steel holds excellent surface finishes (Ra 0.4µm or better) fairly easily. Titanium can also achieve mirror finishes, but because of its “spring back,” holding tight tolerances (e.g., +/- 0.005mm) requires experienced operators who know how to compensate for tool deflection during the finishing pass.

Cost Factors in Machining

Material Costs

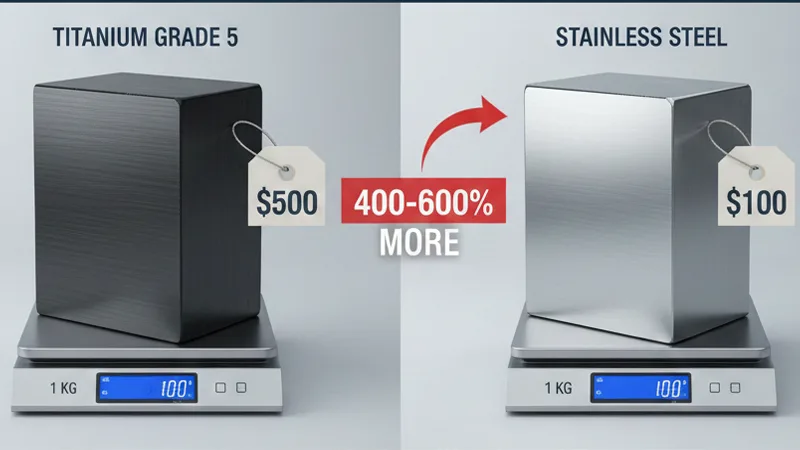

The cost structure of a custom part is a summation of Raw Material + Machine Time + Tooling Consumables.

- Raw Material: Titanium Grade 5 bars can cost 400% to 600% more than Stainless 304 per kilogram.

- “Buy-to-Fly” Ratio: In aerospace, we often machine away 90% of the stock. With titanium, this waste is expensive. With stainless, the scrap loss is financially manageable.

Labor & Machine Time

Machine time is the hidden multiplier.

- Cycle Time: A part that takes 1 hour to machine in Stainless Steel might take 2 to 2.5 hours in Titanium due to the necessary reduction in feed rates and cutting speeds.

- Tooling Cost: A carbide end mill might process 50 stainless parts but only 15 titanium parts before requiring replacement. Titanium machining consumes budget through frequent tool changes and the need for premium, specialized end mills.

| Metal | Raw Material Cost Index | Processing Speed Index | Tooling Cost Index |

| Titanium (Gr 5) | $$$$(Very High) | 0.5x (Slow) | $$$ (High Wear) |

| Stainless (304/316) | $ (Medium) | 1.0x (Standard) | $$ (Moderate) |

Senior Engineer Tip: For high-volume production, the slower cycle time of titanium can create bottlenecks. We often recommend shifting to high-strength precipitation-hardening stainless steels (like 17-4 PH) if the weight penalty is acceptable, purely to reduce production costs.

Performance of Titanium vs Stainless Steel

Strength-to-Weight Ratio

This is the defining metric for aerospace and high-performance automotive applications.

- The Calculation: Specific Strength = Yield Strength / Density.

- The Reality: Titanium Grade 5 offers a specific strength of roughly 200 kN·m/kg, whereas Stainless 316L hovers around 30 kN·m/kg.

If you are designing a drone arm, a robotic end-effector, or a race car suspension component, titanium is the superior choice. It allows you to maximize payload capacity by minimizing structural weight. Stainless steel is simply too dense for weight-critical kinetic applications.

Corrosion Resistance

Both materials are “corrosion resistant,” but the mechanisms and limits differ.

- Titanium: Relies on a spontaneous, tightly packed oxide film. It is one of the few metals immune to chlorides at ambient temperatures. It is the default for heat exchangers in desalination plants.

- Stainless Steel: Relies on Chromium. In environments with low oxygen (stagnant water) or high chlorides (saltwater), the passive layer breaks down, leading to pitting corrosion. Type 316L is better than 304, but Super Duplex grades (like 2507) are needed to approach titanium’s performance in marine settings.

Flexibility & Fracture Strain

- Titanium (Low Modulus): Titanium is twice as elastic as steel. This is a benefit for springs or flexible joints, but a nightmare for slender drive shafts, which may whip or vibrate.

- Stainless Steel (High Ductility): Austenitic stainless steels have incredible fracture toughness. They can deform significantly (elongation >40%) before breaking, making them “safe” failure modes in structural applications. Titanium is more brittle than 316L but much tougher than aluminum.

Biocompatibility & High-Temperature Performance

Medical Applications

Biocompatibility is non-negotiable for implants.

- Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V ELI): This “Extra Low Interstitial” grade is the industry gold standard (ASTM F136). It is bio-inert; the body’s bone tissue will actually grow into the surface (osseointegration). It is non-magnetic, allowing MRI compatibility.

- Stainless Steel (316LVM): Vacuum Melted 316L is used for temporary implants (plates, screws) and surgical tools. However, it contains Nickel, which can trigger allergic reactions in some patients. It is generally not used for permanent joint replacements today.

Industrial Uses

High-Temperature Limits: This is where Stainless Steel often wins.

- Titanium: Limited to approx. 400°C – 550°C. Above this, it becomes highly reactive with oxygen/nitrogen in the air, forming a brittle “Alpha Case” layer that causes surface cracking.

- Stainless Steel: Grades like 310S or Inconel (superalloy) function well up to 800°C – 1100°C. They maintain structural integrity in combustion chambers and industrial furnaces where titanium would oxidize and fail.

Application Recommendations for Custom Metal Parts

Aerospace & Automotive

- Aerospace: Titanium is ubiquitous in airframe structures (landing gear beams, fasteners) and jet engine compressor blades (cold section). The imperative is reducing fuel burn through weight savings (Buy-to-Fly ratio).

- Automotive: Titanium is reserved for the “unsprung weight” of luxury/sports cars (exhausts, suspension springs, valves).

- Stainless Steel: Used in aircraft hydraulic lines and exhaust manifolds where heat resistance is more critical than weight.

Medical Devices

- Implants: Titanium is dominant due to osseointegration and lack of magnetic interference.

- Surgical Instrumentation: Stainless steel (specifically 17-4 PH or 455 custom) is preferred for scalpels, forceps, and drills because it can be hardened to hold a sharp cutting edge, whereas titanium cannot hold an edge well.

Industrial & Chemical Processing

- Chemical Plants: Titanium is specified for handling wet chlorine and bleaching agents where stainless steel dissolves.

- Food Processing: Stainless 304/316 is the global standard (Sanitary Grade). It is easy to sanitize, cheap to replace, and withstands caustic wash-downs. Titanium is overkill and too expensive for standard food hoppers or conveyors.

Consumer Products

- Wearables: Titanium is preferred for premium watch cases and phone bodies because it feels “warm” to the touch (low thermal conductivity) and is hypoallergenic.

- Appliances: Stainless steel provides the classic aesthetic for kitchen goods. It is durable, scratch-resistant (if hardened), and cost-effective for mass consumer goods.

Decision Guide for Material Selection

Quick Reference Table

Use this matrix to guide your initial DFM (Design for Manufacturing) discussions.

| Requirement | Preferred Material | Reasoning |

| Minimize Weight | Titanium | 45% lighter than steel for equal volume. |

| Minimize Cost | Stainless Steel | Lower material cost + faster machining cycle time. |

| Max Service Temp > 600°C | Stainless Steel | Titanium oxidizes and becomes brittle above 550°C. |

| High Stiffness Required | Stainless Steel | Modulus of 200 GPa vs 114 GPa for Titanium. |

| Permanent Human Implant | Titanium | Superior osseointegration and Nickel-free. |

| Magnetic Transparency (MRI) | Titanium | Non-magnetic; safe for medical imaging. |

| Marine/Saltwater Use | Titanium | Superior resistance to pitting; maintenance-free. |

Bullet Point Summary

- Choose Titanium if: The part flies, goes inside a human body, or races on a track. The high cost is justified by the performance gains in specific strength and corrosion immunity.

- Choose Stainless Steel if: The part is structural, stationary, or exposed to extreme heat (>600°C). It is the economical choice for hygiene, general industry, and applications requiring high stiffness.

- Machinability Check: Remember that switching a design from Stainless to Titanium will likely double your machining costs due to slower speeds and higher tooling consumption.

- Surface Finish: Both can achieve high-precision finishes, but Titanium requires more specialized effort to prevent surface galling.

Common Mistakes

- Over-specifying: Designers often specify Titanium Grade 5 when a high-strength Stainless (17-4 PH) would suffice at 30% of the cost, simply because “Titanium sounds better.”

- Galvanic Ignorance: Pairing Titanium fasteners with Aluminum panels without insulation will cause the Aluminum to corrode rapidly (Titanium is noble; Aluminum is anodic).

- Ignoring Thermal Expansion: Titanium expands differently from steel. In tight tolerance assemblies involving mixed metals, thermal cycling can lead to seizing or loss of preload.

FAQ

It is primarily the Specific Strength (Strength-to-Weight ratio). A titanium component can handle the same mechanical loads as a steel counterpart while reducing the system’s total mass by roughly 45%. Additionally, its fatigue limit is exceptionally high, making it ideal for cyclic loading in aerospace.

Cost and heat resistance. Stainless steel (particularly 409 and 304 grades) offers adequate corrosion resistance against exhaust gases and road salts. More importantly, it withstands the thermal cycling of combustion engines without the embrittlement issues that titanium faces at very high temperatures.

In high-end performance vehicles, titanium exhausts are used strictly for weight reduction. Saving 20-40 lbs on an exhaust system lowers the vehicle’s center of gravity and improves power-to-weight ratio. The distinct “metallic” sound is a secondary aesthetic benefit due to the thinner wall sections that titanium allows.

For street performance, Stainless Steel is the logical choice for durability and cost. For track/racing applications where every gram counts, Titanium is superior. However, titanium requires careful welding (back-purging with argon) to prevent failure, making repairs expensive.

Durability, thermal stability, and acoustic tuning. Stainless steel does not oxidize rapidly at exhaust temperatures (unlike mild steel) and maintains structural rigidity. It is also ductile enough to absorb engine vibrations without cracking.

High strength” allows engineers to use less material to support a given load. This enables compact designs (miniaturization) and reduces weight. In dynamic systems, high yield strength ensures the part returns to its original shape after stress, preventing permanent deformation.

Technically, yes, but it is economically inefficient. The cost-to-benefit ratio is poor for a daily commuter. Titanium is best reserved for applications where the performance gains justify the 5x-10x price premium over standard aluminized steel.

Start with the Temperature and Weight constraints.

- Does the part operate above 500°C? If yes -> Stainless/Inconel.

- Is weight critical (aerospace/racing)? If yes -> Titanium.

- Is the budget the primary driver? If yes -> Stainless Steel.

- Is it a permanent medical implant? If yes -> Titanium.