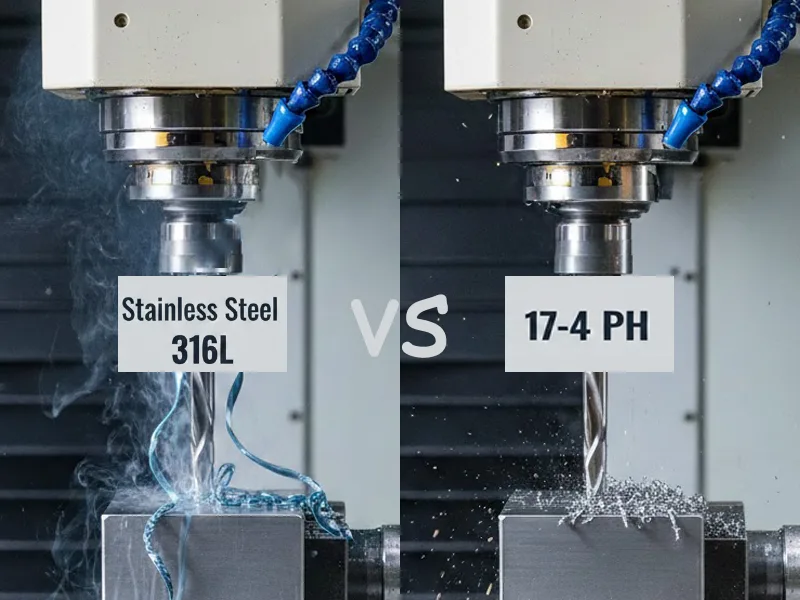

Choosing between Stainless Steel 316L and 17-4 PH is a critical decision for mechanical engineers and machinists. While both are premium alloys, they behave differently on the shop floor and in the field. 316L is the industry standard for corrosion resistance, but presents unique “gummy” machining challenges. 17-4 PH offers superior strength and hardness but can wear tools rapidly if parameters are not optimized.

This comprehensive guide analyses the machinability, cost, and application suitability of these two grades for 2026 manufacturing standards.

Table of Contents

Quick Comparison of Machining Stainless Steel 316L vs 17-4PH

When evaluating machinability, we look beyond simple hardness. We consider chip formation, thermal conductivity, and work-hardening tendencies.

316L Machinability

Machining Stainless Steel 316L requires a strategic approach to overcome its austenitic characteristics.

- Work Hardening: 316L is prone to rapid work hardening. If the cutting tool dwells or rubs, the material surface hardens instantly, causing catastrophic tool failure.

- Gummy Nature: Unlike harder steels, 316L is ductile. This leads to a Built-Up Edge (BUE), where material welds to the cutting insert, degrading the surface finish.

- Thermal Conductivity: 316L has low thermal conductivity, meaning heat stays in the cut zone rather than evacuating with the chip. This thermal concentration accelerates flank wear.

- Chip Control: Chips tend to be long and stringy (nesting birds), requiring aggressive chip breakers or peck cycles to manage.

17-4 PH Machinability

Machining Stainless Steel 17-4 PH presents a different set of challenges driven by its martensitic precipitation-hardening structure.

- Condition Matters: In its Condition A (Solution Annealed) state, 17-4 PH machines are comparable to 304 but with better chip control. However, in hardened states like H900, it behaves like hard tool steel (40-44 HRC), requiring rigid setups and specialized carbide grades.

- Abrasiveness: The presence of hard precipitates (Copper-rich phases) makes 17-4 PH more abrasive than 316L, leading to predictable but faster flank wear.

- Dimensional Stability: 17-4 PH is generally more stable after machining than 316L, as it holds tighter tolerances with less residual stress movement, provided it has been stress-relieved or aged properly.

Tool Wear

Understanding the wear mechanism is key to predicting tool life and estimating part costs.

316L Tool Wear

Tool wear in 316L is characterised by Notch Wear and Built-Up Edge (BUE).

- Notch Wear: This occurs at the depth-of-cut line where the work-hardened “skin” of the previous pass damages the insert.

- Adhesive Wear: At lower speeds, the material sticks to the tool. Using higher surface speeds (within recommended ranges) can generate enough heat to plasticise the chip slightly, reducing adhesion.

- Tool Choice: PVD-coated grades (TiAlN or AlTiN) are preferred over CVD for milling because they offer sharper edge preparations, which are critical for shearing 316L cleanly.

17-4 PH Tool Wear

Wear in 17-4 PH is primarily Abrasive and Thermal.

- Abrasive Wear: The hard martensitic matrix wears down the cutting edge evenly.

- Thermal Cracking: In hardened conditions (H900), intermittent cutting (milling) causes rapid thermal cycling, which can lead to comb cracks in the insert.

- Tool Choice: Tougher carbide substrates are needed for interrupted cuts in 17-4 PH to prevent chipping.

Surface Finish

Surface finish requirements often dictate the manufacturing process flow.

316L Surface Finish

316L is capable of achieving a mirror-like finish but requires careful processing.

- Polishing: Due to its low hardness (~150-190 HB), 316L polishes exceptionally well (electropolishing or mechanical).

- Machining Finish: Achieving a low Ra (roughness average) during machining is difficult due to BUE. High-pressure coolant and sharp wiper inserts are often necessary.

- Post-Processing: Electropolishing is highly recommended for 316L parts in medical or semiconductor applications to remove microscopic peaks and enhance the passive oxide layer.

17-4 PH Surface Finish

17-4 PH finishes well but looks different.

- Grinding: 17-4 PH is an excellent candidate for precision grinding to achieve tight tolerances and low Ra values, especially in the hardened state.

- Appearance: It generally has a darker, more matte grey appearance after passivation compared to the bright silver of 316L.

- Plating: It can be nickel or chrome plated, but the surface must be meticulously cleaned to remove any scale from heat treatment.

Cutting Parameters

Optimising feeds and speeds is the single biggest factor in profitability.

316L Recommended Settings

Cutting Speed (Vc): 100–160 m/min (325–525 SFM) for coated carbide. Running too slow (<60 m/min) increases drag and BUE.

Feed Rate (fn): 0.15–0.30 mm/rev. Crucial: The feed must be heavy enough to cut under the work-hardened layer of the previous pass.

Depth of Cut (ap): Maintain a consistent depth. Tapered cuts (fading out) are dangerous as they force the tool to rub against the hardened skin.

17-4 PH Recommended Settings

Condition A (Annealed):

- Speed: 80–120 m/min (260–400 SFM).

- Feed: 0.10–0.25 mm/rev.

Condition H900 (Hardened ~44 HRC):

- Speed: 30–60 m/min (100–200 SFM). Speed must be reduced significantly to manage heat.

- Feed: 0.05–0.15 mm/rev. Lighter feeds are required to reduce cutting pressure and prevent insert chipping.

Machinability Analysis of 316L and 17-4 PH Stainless Steel

316L Machining Properties

Structure: Face-Centred Cubic (FCC) Austenite. This structure gives 316L its high ductility (40-60% elongation) and toughness, but makes it “gummy”.

Yield Strength: Low (~200-300 MPa), meaning it deforms easily before cutting, generating heat.

Machining Challenges (316L)

Work Hardening: The primary killer of end mills. One second of dwelling can harden the surface to 40+ HRC locally.

Harmonics: Due to lower elasticity, thin-walled 316L parts are prone to chatter.

Coolant Access: The gummy chip can block coolant from reaching the cutting edge.

Applications (316L)

Chemical/Pharma: Fittings, manifolds, and vessels requiring immunity to chlorides.

Marine: Deck hardware and sub-sea sensors.

Medical: Surgical instruments and temporary implants (bone plates).

17-4 PH Stainless Steel Machining Properties

Structure: Martensitic. This Body-Centred Tetragonal (BCT) structure provides high strength and hardness.

Magnetic: Unlike 316L, 17-4 PH is magnetic, which can be useful for magnetic workholding in grinding operations.

Machining Challenges (17-4 PH)

Cutting Force: Requires 20-30% more machine power (spindle torque) than 316L due to higher yield strength.

Tool Deflection: High cutting forces can cause tool deflection, leading to tapered walls if not compensated.

Scale: If machining heat-treated bar stock, the outer “black” scale is extremely hard and abrasive; face mills should enter firmly below this skin.

Applications (17-4 PH)

Aerospace: Landing gear components, actuators, and structural brackets.

Energy: Turbine blades and oil & gas valve stems.

Industrial: Pump shafts and high-strength fasteners.

Performance Factors in Machining Stainless Steel

Tool Life

316L: Tool life is unpredictable. A sudden chip jam or BUE event can chip an edge instantly. Predictable wear curves are harder to achieve.

17-4 PH: Tool life is generally predictable. Wear is gradual (flank wear). This allows for reliable “lights-out” manufacturing if parameters are dialled in.

Surface Quality

316L: Prone to “orange peel” if bent or formed after machining. Machined surfaces can appear cloudy if speeds are too low.

17-4 PH: Produces a crisp, clean cut. Threads (tapping/threading) in 17-4 PH are often cleaner and stronger than in 316L due to less galling.

Cutting Speed and Feed

316L Parameters

Spindle Speed: Optimize for Thermal Management. Too fast = thermal cratering. Too slow = adhesion.

Feed Rate: Optimize for Chip Breaking. Push the feed until the chip breaks into “6s” or “9s” rather than long strings.

17-4 PH Parameters

Spindle Speed: Optimize for Tool Life. Slower speeds preserve the coating on the insert.

Feed Rate: Optimize for Surface Finish. Heavier feeds are possible in the annealed state, but finishing passes in H900 require light skims (0.05-0.1mm).

Practical Machining Tips for 316L and 17-4 PH

316L Machining Tips

Climb Milling Only: Never conventional mill 316L. Conventional milling rubs the tool against the work-hardened surface as it enters the cut.

Variable Helix End Mills: Use unequal helix/flute spacing to disrupt harmonics and prevent chatter.

Through-Spindle Coolant (TSC): Essential for drilling deep holes (>3xD) to evacuate gummy chips and prevent work hardening at the drill tip.

Avoid Dwell: Program the tool path to enter and exit the cut cleanly. Never pause the tool in the cut.

17-4 PH Stainless Steel Machining Tips

Rough in Condition A: Whenever possible, machine the part in the annealed state (Condition A) and heat treat after roughing. Leave 0.010″-0.020″ stock for finish machining after hardening to correct any distortion.

Ceramic Inserts: For turning hardened H900 material, consider whisker-reinforced ceramic inserts for high material removal rates (MRR).

Tap Selection: Use TiCN coated taps designed specifically for hardened steels (~40 HRC) if tapping after heat treatment. Form tapping is risky; cut tapping is preferred for 17-4 PH.

Troubleshooting Machining Issues

316L Issues

Thread Galling: 316L threads often seize (cold weld).

- Fix: Use high-quality moly-based anti-seize or consider thread milling instead of tapping to reduce friction.

Poor Tolerance Holding: Part grows due to heat.

- Fix: Check coolant concentration (aim for 10-12% refractometer reading) to maximize lubricity and cooling.

17-4 PH Issues

Corner Chipping: End mills chipping at the corners.

- Fix: Use a corner radius (bull nose) end mill rather than a sharp corner. The radius distributes the cutting forces better on hard materials.

Warping after Machining:

- Fix: 17-4 PH is relatively stable, but aggressive material removal can induce stress. Add a stress-relief cycle if removing >50% of the stock volume.

Choosing Between 316L and 17-4 PH Stainless Steel

Cost Factors

Material Cost: Historically, 316L is often 10-30% more expensive than 17-4 PH due to the high cost of Molybdenum and Nickel, though markets fluctuate. However, 17-4 PH typically incurs additional costs for heat treatment processes (aging).

Processing Cost: Machining 316L is slower (cycle time) due to lower speeds and more tool changes. 17-4 PH (Condition A) can often be run faster, reducing machine time costs.

Application Needs

Corrosion First? Choose 316L. If the part touches saltwater, acids, or human tissue, 316L is non-negotiable.

Strength First? Choose 17-4 PH. If the part is a shaft, gear, or load-bearing bracket, 17-4 PH (H900) offers 3-4x the yield strength of 316L.

Shop Capabilities

Rigidity: If your machine shop uses older, less rigid equipment (e.g., loose ball screws), 17-4 PH will be difficult to hold tolerance on. 316L is more forgiving of machine slop but less forgiving of poor tooling.

Heat Treat: Does your shop have an oven? 17-4 PH allows you to increase value in-house by machining and then aging parts (e.g., 482°C for 1 hour for H900) without sending them out.

Decision Guide

Select 316L if:

- Environment: Marine, Chemical, Medical.

- Property: Non-magnetic, high ductility.

- Constraint: No heat treatment available.

Select 17-4 PH if:

- Environment: High mechanical stress, wear surfaces.

- Property: Magnetic, high hardness (up to 44 HRC).

- Constraint: Tight tolerances required (better stability).

FAQ

The main difference is their microstructure and strengthening mechanism. 316L is an austenitic stainless steel that relies on Molybdenum for superior corrosion resistance but has low yield strength (~30 ksi). 17-4 PH is a martensitic precipitation-hardening steel that offers high yield strength (~170 ksi in H900) and hardness but lower corrosion resistance.

17-4 PH is one of the most popular metal 3D printing materials because it is highly responsive to post-process heat treatment. A printed part can be strengthened significantly (to ~40 HRC) with a simple ageing cycle. 316L printed parts remain soft and are primarily used for corrosion resistance.

Generally, no. While 17-4 PH has “good” corrosion resistance (comparable to 304), it is susceptible to crevice corrosion and pitting in stagnant seawater. For true marine service, 316L (or Duplex 2205) is the required standard.

17-4 PH has a vastly superior strength-to-weight ratio. Since both metals have similar density (~7.8 g/cm³), the 3-4x strength advantage of 17-4 PH allows engineers to design much thinner, lighter components for the same load-bearing capacity.

17-4 PH contains approximately 17% Chromium, 4% Nickel, and 4% Copper (plus Niobium/Columbium). The Copper precipitates during heat treatment are what give the alloy its incredible strength (Precipitation Hardening).

“Gumminess” refers to the material’s high ductility and tendency to adhere to the cutting tool. 316L does not chip away cleanly; it tears and drags. This adhesion creates a Built-Up Edge (BUE), where the workpiece material welds to the tool, altering the cutting geometry and degrading the finish.